Vande Mataram

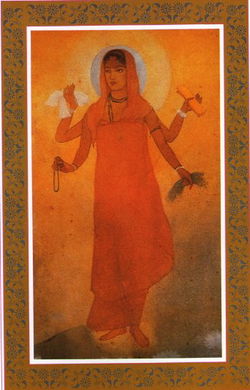

Vande Mataram (Bengali script: বন্দে মাতরম্; Devanagari: वन्दे मातरम्; Vande Mātaram "I do homage to the mother";[1] ) is a poem in the 1882 novel Anandamatha by Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay. It is written in a mixture of Bengali and Sanskrit.[2] It is a hymn to the goddess Durga, identified as the national personification of India. It came to be considered the "National Anthem of Bengal",[3] and it played a part in the Indian independence movement, first sung in a political context by Rabindranath Tagore at the 1896 session of the Indian National Congress[4]. In 1950, its first two verses were given the official status of "national song" of the Republic of India,[4] distinct from the national anthem of India Jana Gana Mana. Many Muslim organizations in India have declared fatwas against singing Vande Mataram, due to the song's giving a notion of worshiping Mother India, which they consider to be shirk (idolatry).[5]

A commonly cited English language translation of the poem, Mother, I bow to thee!, is due to Sri Aurobindo (1909).[6] The poem has been set to a large number of tunes. The oldest surviving audio recordings date to 1907, and there have been more than a hundred different versions recorded throughout the 20th century. In 2002, BBC World Service conducted an international poll to choose ten most famous songs of all time. Around 7000 songs were selected from all over the world. Vande Mataram, in a version by A. R. Rahman, was second in top 10 songs.[7]

Contents |

History and significance

Composition

It is generally believed that the concept of Vande Mataram came to Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay when he was still a government official under the British Raj, around 1876.

Chattopadhyay wrote the poem in a spontaneous session using words from Sanskrit and Bengali. The poem was published in Chattopadhyay's book Anandamatha (pronounced Anondomôţh in Bengali) in 1882.[2] Jadunath Bhattacharya was asked to set a tune for this song just after it was written.[2]

Indian independence movement

"Vande Mataram" was the national cry for freedom from British rule during the freedom movement. Large rallies, fermenting initially in Bengal, in the major metropolis of Calcutta, would work themselves up into a patriotic fervour by shouting the slogan "Vande Mataram", or "Hail to the Mother(land)!". The British, fearful of the potential danger of an incited Indian populace, at one point banned the utterance of the motto in public forums, and imprisoned many freedom fighters for disobeying the proscription. Rabindranath Tagore sang Vande Mataram in 1896 at the Calcutta Congress Session held at Beadon Square. Dakhina Charan Sen sang it five years later in 1901 at another session of the Congress at Calcutta. Poet Sarala Devi Chaudurani sang the song in the Benares Congress Session in 1905. Lala Lajpat Rai started a journal called Vande Mataram from Lahore.[2] Hiralal Sen made India's first political film in 1905 which ended with the chant. Matangini Hazra's last words as she was shot to death by the Crown police were Vande Mataram[8]

In 1907, Bhikaiji Cama (1861-1936) created the first version of India's national flag (the Tiranga) in Stuttgart, Germany, in 1907. It had Vande Mataram written on it in the middle band.[9]

Adoption as "national song"

Tagore's Jana Gana Mana was chosen as the National Anthem of the 1947 Republic of India. Vande Mataram was rejected on the grounds that Muslims, Christians, Parsis, Sikhs, Arya Samajis and others who opposed idol worship felt offended by its depiction of the nation as "Mother Durga", a Hindu goddess. Muslims also felt that its origin as part of Anandamatha, a novel they felt had an anti-Muslim message.

The designation as "national song" predates independence, dating to 1937. At this date, the Indian National Congress discussed at length the status of the song. It was pointed out then that though the first two stanzas began with an unexceptionable evocation of the beauty of the motherland, in later stanzas there are references where the motherland is likened to the Hindu goddess Durga. Therefore, INC decided to adopt only the first two stanzas as the national song.

The controversy becomes more complex in the light of Rabindranath Tagore's rejection of the song as one that would unite all communities in India. In his letter to Subhash Chandra Bose (1937), Rabindranath wrote:

"The core of Vande Mataram is a hymn to goddess Durga: this is so plain that there can be no debate about it. Of course Bankimchandra does show Durga to be inseparably united with Bengal in the end, but no Mussulman [Muslim] can be expected patriotically to worship the ten-handed deity as 'Swadesh' [the nation]. This year many of the special [Durga] Puja numbers of our magazines have quoted verses from Vande Mataram - proof that the editors take the song to be a hymn to Durga. The novel Anandamath is a work of literature, and so the song is appropriate in it. But Parliament is a place of union for all religious groups, and there the song cannot be appropriate. When Bengali Mussulmans show signs of stubborn fanaticism, we regard these as intolerable. When we too copy them and make unreasonable demands, it will be self-defeating."

In a postscript to this same letter, Rabindranath says:

"Bengali Hindus have become agitated over this matter, but it does not concern only Hindus. Since there are strong feelings on both sides, a balanced judgment is essential. In pursuit of our political aims we want peace, unity and good will - we do not want the endless tug of war that comes from supporting the demands of one faction over the other." [10]

Rajendra Prasad, who was presiding the Constituent Assembly on January 24, 1950, made the following statement which was also adopted as the final decision on the issue:

- The composition consisting of words and music known as Jana Gana Mana is the National Anthem of India, subject to such alterations as the Government may authorise as occasion arises, and the song Vande Mataram, which has played a historic part in the struggle for Indian freedom, shall be honored equally with Jana Gana Mana and shall have equal status with it. (Applause) I hope this will satisfy members. (Constituent Assembly of India, Vol. XII, 24-1-1950)

The two verses adopted as "national song" read as follows:

| In Aurobindo Ghose's translation:[11] | in IAST: | Bengali romanization: |

|

I bow to thee, Mother, |

vande mātaram |

bônde matorom |

2006 controversy

On August 22, 2006, there was a row in the Lok Sabha of the Indian Parliament over whether singing of Vande Mataram in schools should be made mandatory. The ruling United Progressive Alliance (UPA) coalition and Opposition members debated the Government's stance that singing the national song Vande Mataram on September 7, 2006, to mark the 125th year celebration of its creation should be voluntary. This led to the House's being adjourned twice. Human Resources Development Minister Arjun Singh noted that it was not binding on citizens to sing the song. Arjun Singh had earlier asked all state governments to ensure that the first two stanzas of the song were sung in all schools on that day. Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) Deputy Leader V. K. Malhotra wanted the Government to clarify whether singing the national song on September 7 in schools was mandatory or not. On August 28, targeting the BJP, Congress spokesman Abhishek Singhvi said that in 1998 when Atal Behari Vajpayee of the BJP was the Prime Minister, the BJP supported a similar circular issued by the Uttar Pradesh government to make the recitation compulsory. But Vajpayee had then clarified that it was not necessary to make it compulsory.[12]

On September 7, 2006, the nation celebrated the national song. Television channels showed school children singing the song at the notified time.[13] Some Muslim groups had discouraged parents from sending their wards to school on the grounds, after the BJP had repeatedly insisted that the national song must be sung. However, many Muslims did participate in the celebrations[13].

View of Muslim institutions

Muslim institutions in general, see Vande Mataram in a negative light.[5] Though a number of Muslim organizations and individuals have opposed Vande Mataram being used as a "national song" of India, citing many religious reasons, some Muslim personalities have admired and even praised Vande Mataram as the "National Song of India" . Arif Mohammed Khan, a former Union Minister in the Rajiv Gandhi government, wrote an Urdu translation of Vande Mataram which starts as Tasleemat, maan tasleemat.[14]

All India Sunni Ulema Board on Sept 6, 2006, issued a fatwa that the Muslims can sing the first two verses of the song. The Board president Moulana Mufti Syed Shah Badruddin Qadri Aljeelani said that "If you bow at the feet of your mother with respect, it is not shirk but only respect."[15] Shia scholar and All India Muslim Personal Law Board vice-president Maulana Kalbe Sadiq stated on Sept 5, 2006 that scholars need to examine the term "vande." He asked, "Does it mean salutation or worship?"[16]

View of Sikh institutions

Shiromani Gurudwara Parbandhak Committee or SGPC, the paramount representative body in the Sikh Panth, requested that the Sikhs not sing "Vande Mataram" in the schools and institutions on its centenary on Sept 7, 2006[17]. SGPC head, Avtar Singh Makkar, expressed concern that "imposing a song that reflected just one religion was bound to hurt the sentiments of the Muslims, Sikhs, Christians and other religious minorities. The DSGMC (Delhi Sikh Gurudwara Management Committee) has called singing of "Vande Mataram" against Sikh tenents[18] as the Sikhs sought "sarbat da bhala" (universal welfare) and did not believe in "devi and devta"[19]. DSGMC head H. S. Sarna also added that the song "Vande Mataram" had been rejected long before by well known freedom fighter Sikhs like Baba Kharak Singh and Master Tara Singh[20].

View of Christian institutions

Fr. Cyprian Kullu from Jharkhand stated in an interview with AsiaNews: "The song is a part of our history and national festivity and religion should not be dragged into such mundane things. The Vande Mataram is simply a national song without any connotation that could violate the tenets of any religion."[21] However, some Christian institutions such as Our Lady of Fatima Convent School in Patiala did not sing the song on its 100th anniversary as mandated by the state.[22] Christians make a distinction between "veneration" and "worship," and even though the song falls into neither of these categories, some Christians may have declined to sing the national song because of their understanding of its intention and content.

Performances and interpretations

A number of lyrical and musical experiments have been carried out, and many versions of the song were created and released throughout the 20th century and into the 21st century. Many of these versions have employed traditional South Asian classical ragas. Versions of the song have been visualized on celluloid in a number of films, including Leader, Amar Asha, and Anandamath. It is widely believed that the tune set for All India Radio station version was composed by Ravi Shankar.[2]

See also

-

Aurobindo Ghose: Vande Mataram on Wikisource

Aurobindo Ghose: Vande Mataram on Wikisource

-

Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay: वन्दे मातरम् on Wikisource

Bankimchandra Chattopadhyay: वन्दे मातरम् on Wikisource

- Indian National Anthem

- Saare Jahan Se Achcha

- Bharat Mata

- Vande Mataram (album)

References

- ↑ Sanskrit vandate (1st class, atmanepadam) "to praise, celebrate, laud, extol; to show honour, do homage, salute respectfully or deferentially, venerate, worship , adore" (Monier Williams)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Suresh Chandvankar, Vande Mataram (2003) at Musical Traditions (mustrad.org.uk)

- ↑ Sri Aurobindo commented on his English translation of the poem with "It is difficult to translate the National Song Of India into verse in another language owing to its unique union of sweetness, simple directness and high poetic force." cited after Bhabatosh Chatterjee (ed.), Bankim Chandra Chatterjee: Essays in Perspective, Sahitya Akademi, Delhi, 1994, p. 601.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "National Symbols of India". Government of India. http://india.gov.in/knowindia/national_song.php. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 [1] "Fatwa against Vande Mataram"

- ↑ Sri Aurobindo, Bande Mataram and a lecture on the hidden meaning of that song (1908, 1909).

- ↑ The Worlds Top Ten — BBC World Service

- ↑ Chakrabarty, Bidyut (1997). Local Politics and Indian Nationalism: Midnapur (1919-1944). New Delhi: Manohar. pp. 167.

- ↑ p2

- ↑ (Letter #314, Selected Letters of Rabindranath Tagore, edited by K. Datta and A. Robinson, Cambridge University Press)

- ↑ Karmayogin, 20 November, 1909

- ↑ "BJP vs Congress: It’s Vande vs Kandahar". Asian Age. 2006-08-28. http://www.asianage.com/main.asp?layout=2&cat1=5&cat2=154&newsid=243846&RF=DefaultMain.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Indians celebrate national song". BBC News. September 7, 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/5324398.stm. Retrieved May 27, 2010.

- ↑ outlookindia.com

- ↑ Now, a fatwa to sing Vande Mataram-Hyderabad-Cities-The Times of India

- ↑ Muslims will sing, but omit Vande

- ↑ http://www.rediff.com/news/2006/sep/06vande1.htm

- ↑ http://www.tribuneindia.com/2006/20060907/delhi.htm#11

- ↑ http://www.tribuneindia.com/2006/20060907/delhi.htm#11

- ↑ http://www.tribuneindia.com/2006/20060907/delhi.htm#11

- ↑ INDIA India: fatwa against national song celebrating motherland - Asia News

- ↑ PunjabNewsline.com - Sikhs and christians in Punjab stayed away from 'Vande Matram'

- Sabyasachi Bhattacharya, Vande mataram, the biography of a song, Penguin Books, 2003, ISBN 9780143030553.

External links

- Vande Mataram Sung by Lata Mangeshkar in Anand Math

- Vande Mataram Sung by Hemant Kumar Mukhopadhaya in Anand Math

- Download the most simple and most elegant version of Vande Mataram from the National Portal of India, Government of India.

- Vande Mataram against Sikh tenets

- "How Secular is Vande Mataram?" AG Noorani on the controversy

- Boycott threat over Indian song - BBC

- 1937 Congress Resolution on validity of Muslim objection to this song

- "Vande Mataram and Muslims" - Islamic Voice (magazine)

- Vande Matram is back as a handle to beat Muslims with

- Historical perspective from Islamic Voice

|

|||||||